Background

In 1954, after debating the case, Brown v. Topeka Board of Education, the United States Supreme Court ruled that segregation of public schools violated the Constitution by denying the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. The Brown ruling had the greatest impact in southern states, where school segregation was "de jure" or implemented according to law. In many northern cities like Boston, segregation of schools was not codified as law but racial segregation of public schools still occurred. In Boston, this “de facto” (by fact) segregation happened in part because economic disparities affected neighborhood demographics and these disparities increased after WWII. African-Americans and whites settled into different neighborhoods; public schools located in those neighborhoods were attended by predominantly African-Americans or whites who lived nearby. Since schools grew increasingly segregated in Boston the 1950s and 1960s--not by law but by circumstance--public schools in Boston were not actively desegregated after the Brown decision.

In 1961, a Boston activist, Ruth Batson, led a series of meetings between the Education Committee of the NAACP and the Education Committee on the Boston Public Schools (CBPS) to investigate the situation in Boston's schools. In the mid-1960s, some African American parents began boycotting Boston schools for the wide discrepancies in districts. Black school districts, they found, were overcrowded, understaffed, often dirty, and lacking in supplies and teaching tools while white districts had newer buildings, more teachers, ample supplies, and newer technology. According to CBPS reports, schools in black districts received only 65 percent of the per-student funding that schools in white districts received [1]. The Massachusetts State Education Coordinator appointed the Advisory Committee on Racial Imbalance and Education to investigate the allegations of inequity and racial segregation of Boston's public education system. In April 1965, the committee released a report detailing racial division within Boston's public schools. Finding that over half of the city's African American students attended 28 schools which were at least 80% black and that sixteen schools of the schools were 96% black, the committee concluded that such “racial imbalance” (the term they substituted for de facto segregation) “represents a serious conflict with the American creed of equal opportunity.”[2]. To redress the de facto segregation occurring in Boston public schools, they recommended that African American students be bused from their urban neighborhoods into surrounding suburbs that were inhabited predominantly by whites. Busing students, they believed, would help to achieve the goal of the newly-passed Massachusetts Racial Imbalance Act (1965): to promote racial and ethnic diversity in public schools. The Boston School Committee rejected the recommendation. In 1966, the Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity (METCO) was formed. The grassroots organization addressed the issue of de facto segregation and attempted to satisfy the aims of the Racial Imbalance Act in a peaceful and voluntary manner.

With goals of improving educational opportunities to urban students, decreasing the racial separation of urban and suburban schools, and diminishing de facto segregation of schools, METCO’s program bused thousands of African American children from Boston to suburban schools. Despite its success, METCO functioned as a voluntary program on a comparatively small scale; the majority of public schools were not fully integrated. On March 14, 1972, the NAACP filed a class action lawsuit against the Boston School Committee on behalf of Tallulah Morgan and other concerned parents disturbed by the inequities their children encountered due to de facto segregation of schools. Led by Morgan, the plaintiffs in this case alleged that the Boston School Committee intentionally violated the 14th Amendment of the U. S. Constitution.

The case, formally titled Talullah Morgan et al v. James Hennigan et al, was assigned to federal judge Wendell Arthur Garrity, Jr. On June 21, 1974, after months of testimony and investigation, Judge Garrity found that the Boston School Committee had intentionally endorsed systemic segregation of the Boston Public Schools. The U. S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit unanimously upheld Garrity’s ruling and ordered the Boston School Committee to design a permanent school desegregation plan that addressed the placement of students and teachers, facility improvement procedures, and the use of busing on a citywide basis.

When the Boston School Committee failed to present an adequate plan, the federal court began desegregating the Boston public schools by busing students to schools outside of their neighborhoods. Garrity’s decision, especially the implementation of busing public school students to new schools, provoked heated reactions from residents of Boston and sparked much controversy. Morgan v. Hennigan was commonly referred to as “Boston Schools Desegregation Case” and became known colloquially in Boston as “the Garrity decision” or “forced busing.”

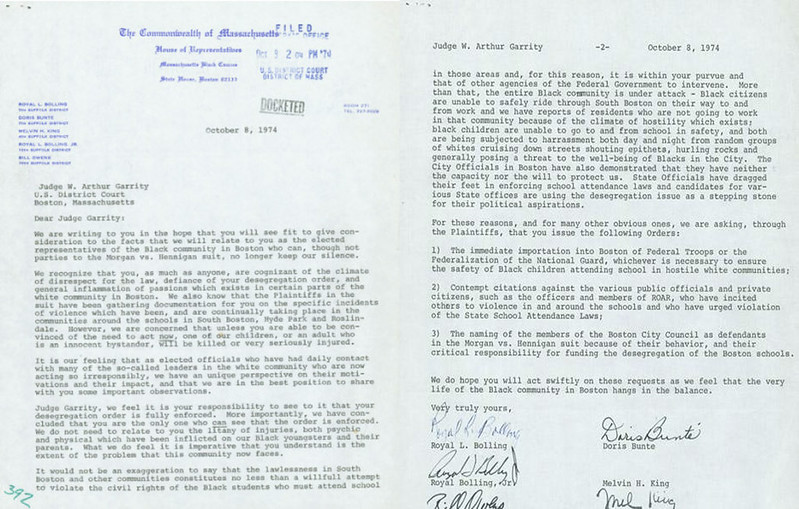

As exhibits on this site showcase, city and state officials were deluged with thousands of letters expressing the heated reactions of parents, teachers, students, and local organizations. As other exhibits explore, Judge Garrity also received thousands of letters from Boston's inhabitants, some protesting and others praising his decision. The letter below (courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration [NARA] in Boston), echoes the sentiment of thousands of letters written by African Americans who, feeling unprotected by Boston city officials, appealed directly to Garrity.

Petitioning Garrity in 1975, Boston politicians and activists, including Bruce Bolling, Doris Bunte, and Melvin H. King, starkly described that in South Boston, “black children are unable to go to and from school in safety . . . are being subjected to harassment both day and night from random groups of whites cruising down the streets shouting epithets, hurling rocks and generally posing a threat to the well-being of Blacks in the city." They demanded:

Judge Garrity… it is your responsibility to see to it that your desegregation order is fully enforced… we do hope you act swiftly on these requests as we feel that the very life of the Black community in Boston hangs in the balance.”

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Boston houses the federal records pertaining to the case, including copies of letters sent by government officials to Garrity. See: Civil Action Case Files, 1938-1995 for more materials and view select digitized files related to Morgan v. Hennigan.

De facto segregation in education presented a thorny problem in Boston long before the Garrity decision to integrate schools by busing students outside of their neighborhoods sparked controversy, fear, violence, and attracted widespread international media attention. And the legacy of de facto segregation in Boston persisted long after the 1970s, as exhibits on this site illustrate. More information about the history of civil rights in America and the integration of Boston's schools may be found online; please see the Online Resources on this site for a list of digital projects. All of the archival collections used on this site contain additional primary source materials. Additionally, the books listed below provide contextual information about the history of desegregation of Boston Public Schools.

Photograph credits

Photograph of Ruth Batson, ca.1961, courtesy of Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University. Rights status is not evaluated.

Portrait of Wendell Arthur Garrity, Jr. ca.1985, courtesy of Holy Cross Magazine, Sept. 1999. Rights status is not evaluated. See full obituary here.

Select secondary sources related to desegregation of Boston Public Schools

Ruth Batson, The Black Educational Movement in Boston: A Sequence of Historical Events: a Chronology (Boston, MA: Northeastern University, School of Education), 2001.

Laura Shana Kohl, "The Response of the Catholic Church to the Desegregation of the Boston Public Schools, 1973-1976" (Cambridge, MA: A.B. Honors Thesis, Harvard University), 1987.

Kofi Lomotey and Charles Teddlie. ed., Forty Years After the Brown Decision: Implications of School Desegregation for U.S. Education (New York: AMS Press), 1996.

J. Anthony Lukas, Common Ground: A Turbulent Decade in the Lives of Three American Families (New York: Alfred A. Knopf), 1985.

Jim Vrabel, A People's History of the New Boston (Amherst : University of Massachusetts Press), 2014.

Notes

[1] Vrabel, A People's History, 49-50.

[2] Lukas, Common Ground, 130.