Browse Exhibits (5 total)

Kathleen Sullivan: "That Girl" Who Shook Things Up

“So it is going to be,” she said softly, “and things are going to change.”

–Kathleen Sullivan [1]

Kathleen Sullivan joined the Boston School Committee (BSC) in 1974 and served for six years, during the height of what became known as the busing crisis. Though Sullivan reformed the committee during those years, history remembers another woman, Louise Day Hicks, as the leader of the Boston School Committee during the tumultuous desegregation years. Hicks, outspoken founder of the anti-busing group ROAR, led the committee in resisting the Racial Imbalance Act of 1965 in the decade prior to busing. The following exhibit tells the story of moderate Kathleen Sullivan and how she changed Boston’s school system during one the city’s most tense periods.

Kathleen Sullivan entered the 1973 race for the BSC as a complete newcomer but, unlike most people who ran for election to the committee, she had taught in public schools in both in New York and Boston. Sullivan differed from Hicks in many wars. While they both came from affluent families and went to school for education, Hicks never taught in Boston schools. She grew up in South Boston, an area known for its fierce local pride and one of the most vocal anti-busing communities. Sullivan grew up outside of Boston, and taught in Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant before teaching in Dorchester’s John Marshall School. Her concern over student education propelled her into the race for school committee and allowed for her reelection in both 1975 and 1977.

This exhibit uses documents from the Boston City Archives and the National Archives to demonstrate how an outsider entered the Boston School Committee in 1974 and completely challenged the status quo, altering the committee for the better. It explores key phases of Sullivan’s work, including how Sullivan got elected in 1973, the reasons why she continued to get elected, her interactions with her constituents, her leadership as President of the BSC in 1977, and her attempted run for Senate in 1978. Popular memory associates Louise Day Hicks and anti-busing with the BSC. By taking a look at Kathleen Sullivan’s role in the move to desegregate Boston Public Schools, we gain an often overlooked narrative because of how she did not quite fit in with her contemporaries at the time.

[1] Jeff McLaughlin, “Teacher Kathy Sullivan learns how to win,” The Boston Globe, November 7, 1973, 34.

Back to Square One: Racial Imbalance in the Boston Public Schools

racial: ra·cial│\ˈrā-shəl\ │adj. (1862) 1: of, relating to, or based on a race 2: existing or occurring between races

imbalance: im·bal·ance │\(ˌ)im-ˈba-lən(t)s\│n. (ca. 1890) lack of balance: the state of being out of equilibrium or out of proportion*

Alone, these two words invoke feelings of mixed emotions and differing opinions. When combined, however, they create a phrase powerful enough to alter the history and reputation of a city and its residents. Up until the 1960s, the de facto segregation of the Boston neighborhoods and the resulting segregation within the schools occurred without widespread attention. This all changed with the construction of the phrase, "racial imbalance." Through photographs, primary documents, and the text, this exhibit focuses on exploring the initial attempt to desegregate the Boston Public Schools in the 1960s, before Judge Garrity's forced busing order.

Before exploring this exhibit, what do you think "racial imbalance" means in regards to a school? Now, imagine that someone asked you to draw up a plan to resolve a problem stemming from racial imbalance in a school. How would you approach it? Before you answer, try to keep in mind a few things. Who is in charge of the school committee? What is the majority public opinion of the city's residents? What are your own viewpoints? Will your plan affect your life or only the lives of others? These are all questions that need addressing in this situation. Oh, and one last thing: you live in the “Cradle of Liberty”, the reputation of your city is at stake, and the whole world is watching, waiting, and judging.

With this in mind, explore these next few pages to discover the roots of the chaos and controversy surrounding the desegregation of the Boston Public Schools.

*Merriam Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary 10th edition

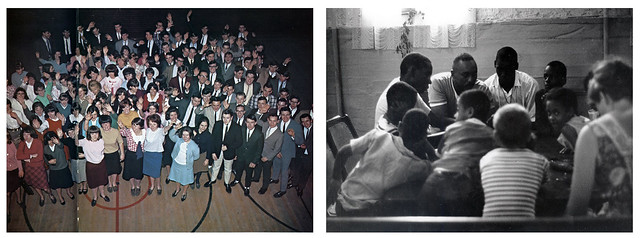

Photo sources: Boston City Archives (left), Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections (right)

ROAR: The Anti-Busing group with the Loudest Voice

Every historical event has numerous perspectives and opinions; however, the perspective with the loudest voice often gains the most attention. In the case of the historical event known as “forced busing” in Boston, those with the loudest voices seemed to be the citizen groups. The group with the loudest voice was arguably the most militant, radically conservative, and most popular anti-busing group during this time: ROAR.

An acronym for Restore Our Alienated Rights, ROAR was a conservative group that fiercely protested the federally-mandated order to integrate Boston Public Schools. Opposed to what they dubbed the “forced busing” of Boston's public school students, the group staged formal, sometimes violent protests and remained active from 1974 until 1976.

ROAR began as a small, informal gathering of opinionated people--mostly women--who wanted to voice their concerns about busing. Over time, their force grew. They shouted that their rights as parents were being taken away because of the efforts to correct the racial imbalance of Boston Public Schools by busing students to other school districts. Within only a few months, under the leadership of Louise Day Hicks, ROAR rapidly grew into the fiercest, loudest anti-busing group. Modeling the the tactics of early civil rights activists, ROAR maintained they were the only voice that spoke for the rights of children and concerned the parents.

ROAR ended within two years of its creation; however, despite its short lifespan, it is the most-remembered anti-busing organization both during and beyond the Boston busing movement.

This exhibit explores the anti-busing organization ROAR by presenting the group in small, manageable sections so that readers may better understand this anti-busing group. Although this radical conservative group no longer exists, the legacy it left behind remains alive in the United States. History repeats itself, and through learning about this group, you might be able to apply the message to the present.

Collisions of Church & State: Religious Perspectives on Boston's School Desegregation Crisis

Mandatory school desegregation in Boston precipitated a wave of activism, advocacy, and debate by religious institutions and their constituents. Whether outraged or delighted by the implications of busing in public schools, individuals often understood and expressed their positions through the lens of their faith. Some believed desegregation to be an issue of justice, and thus in keeping with Biblical teachings. Others considered the "forced busing" of white children to be evil and abusive, invoking faith-based opposition to what they considered an anti-Christian social movement. Regardless of their support or disapproval of busing, people employed a multiplicity of religious interpretations to support their stance.

People from within and beyond Boston addressed these various religious perspectives in their writings to local officials. Often, they wrote to express their views on the morality of busing. In other cases, church officials wrote to invite city or state leaders to events or political rallies relevant to their cause. Collectively, religious sentiments in public records speak to the existence of an active and passionate response to school desegregation by Christians throughout the Boston area and the greater United States.

This exhibit examines the ways in which Catholics and Protestants approached the issue of mandatory busing vis-à-vis the role of government. The three pages collectively showcase documents sent to and from Judge W. Arthur Garrity, Mayor Kevin White, and Councilwoman Louise Day Hicks that in some way address the role of church or religion during the crisis. Prayers for Justice and Peace contains letters, invitations, and cards sent to Judge Garrity in response to his decision to desegregate Boston's schools in Morgan v. Hennigan. "God Is Giving You a Chance" catalogs letters of religious support for desegregation sent to Louise Day Hicks and Mayor White. Finally, "Joan of Arc of Boston" shares correspondence of Louise Day Hicks regard-ing faith, church, and her anti-busing coalition, R.O.A.R.

Selected materials represent a large geographic range of correspondence; some were sent from Boston, while others originated as far away as San Francisco (see the Geographic Distribution Map for a spatial visualization). The collection is limited to the years 1973-1975, which saw the height of responses to busing. Names and other identifying information have been redacted from all documents to protect the privacy of their authors or recipients.

Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity (METCO): Solving Racial Imbalance in Boston Public Schools

The goal of this exhibit is to illustrate how METCO and its administrators worked to reach out to organizations making the transition easier for black students and how organizations were reacting to the role that METCO ultimately played in desegregation.

The exhibit highlights that while METCO was focused on monitoring and resolving racial imbalance issues in school placement, there were also problems that needed to be dealt with internally. Documents included in the exhibit range from letters of petition from different organizations to Boston officials that were monitored and sometimes filtered through METCO. Letters from executives in METCO to officials in the Boston School system imploring them to aid in making school desegregation an easier process for students and organizations helping in communities. Some of these letters will show not only the frustrations of grassroots organizations and major organizations like the NAACP branch of Boston, but also the problems faced by METCO in regards to representation of their work with desegregation and student placement.