Browse Exhibits (2 total)

Ruth M. Batson: Mother - Educator - Civil Worker

“… a woman who has given her heart, her strength and her militant spirit in the true tradition of Harriet Tubman.”

~ The Black Educational Movement in Boston: A Sequence of Historical Events (2001)

Ruth M. Batson (1921-2003) was an African American woman and a lifelong Bostonian who stood up for her beliefs. For more than thirty years she championed fair and equal education for Boston’s public school children and for the civil rights of African Americans. On printed flyers and in newspaper advertisements for her 1951 Boston School Committee campaign, Batson lists “Mother - Educator - Civil Worker” as her three most important qualifications for this committee. These characteristics propelled her into a life of public service where she fought for a better education for children and for the African American population of Boston. The core values she learned as a young child would became a motivation for her tireless work for justice.

In order to bring Ruth Batson’s story forward, we must start by looking backward. In 1975, a series of articles in The Sunday Boston Herald Advertiser appeared regarding the desegregation of the Boston Public Schools. The reporters, Alan Eisner and Frank Thompson, credit Ruth Batson as the person who initially championed changes in Boston’s School system. Batson, indeed, stood before the Boston School Committee in June of 1963 to read a statement from the NAACP demanding changes be made to the Boston Public School system. A cohesive fight to attain Civil Rights spread through out the nation movement a decade earlier, so what was Batson doing before she stepped onto the public stage in 1963?

In December 1950, The Boston Traveler reported that members from a group called “The Parents Federation of Greater Boston,” headed by Ruth Batson, held a protest at Boston’s City Hall attempting to talk to Mayor John Hynes regarding the deplorable conditions in the city’s schools. With in a few short months, Batson ran an unsuccessful campaign for a seat on the Boston School Committee. By 1953 Batson had approached the NAACP for help with this issue and found herself the chairman of the Public Education Sub-Committee of the NAACP Boston Branch. At a time when most American women were content to be a wife, mother and homemaker, Batson stepped out of this traditional female role to speak out and advocate for much needed changes to Boston’s public schools and for civil rights long before there was a “movement” to speak of in Boston.

Ruth M. Batson continuously worked in some capacity for almost thirty years to bring about changes to the Boston Public School system. She started out a young mother trying to improve her children’s neighborhood school and ended up improving all the schools of Boston. This exhibit focuses on Batson’s work regarding the desegregation of Boston Public Schools. A brief biography establishes the foundation of Batson’s belief system and demonstrates her motivation to fight for change in Boston’s public school system. This biography reveals the many components of her life and put into perspective her family, interests, and a varied career fighting for education and civil rights.

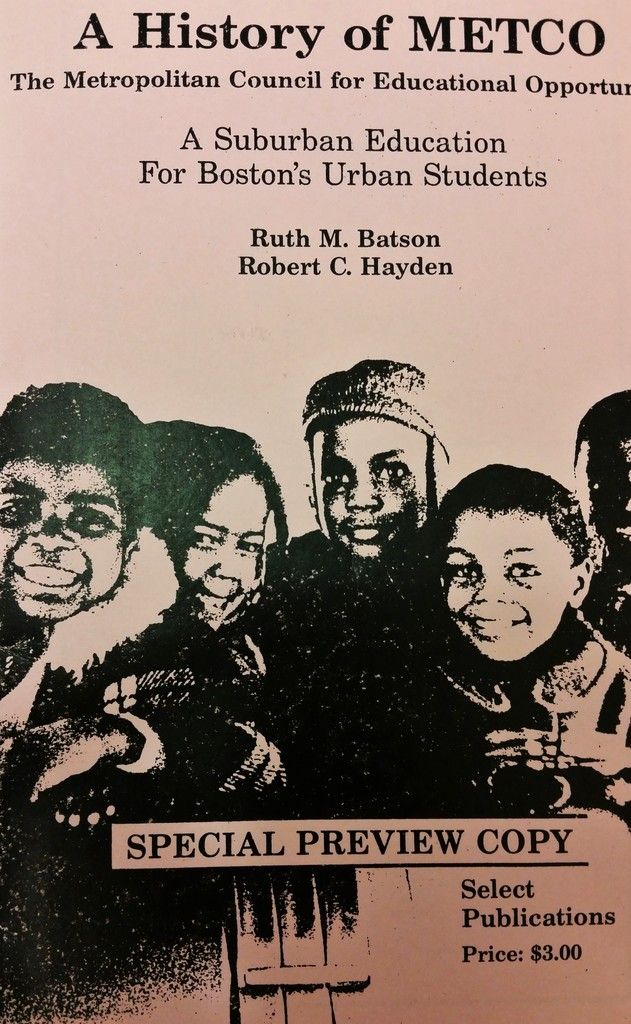

The remaining three parts of this exhibit explore Batson’s direct work regarding the desegregation of Boston’s schools. The first explores her work on the Public Education Committee of the NAACP Boston Branch. Her work included gathering information on the condition of Boston schools, advocating for parents and children, and finally becoming a spokesperson to call for necessary changes in the schools. The second focuses on Batson’s career at the Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity (METCO). She was involved with this program from its inception, helping to develop it from an idea to a thriving program. She started out on a steering committee and went on to become its executive director. The last looks at Batson’s involvement working behind the scenes during the early days of forced busing. From her job at Boston University and as a committee member at Freedom House, she worked to support children and families during this turbulent time.

____________________________

Sources

Alan Eisner and Frank Thompson. “The Anatomy of Boston’s School Crisis,” The Sunday Boston Herald Advertiser (August 10, 1975): section 5, page 1.

“Hynes to Run for Mayor Again: City Head Tips Hand in Seeking to Calm Group Irate Over Schools,” The Boston Herald Traveler (December 28, 1950): 1, 32.

Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity (METCO): Solving Racial Imbalance in Boston Public Schools

The goal of this exhibit is to illustrate how METCO and its administrators worked to reach out to organizations making the transition easier for black students and how organizations were reacting to the role that METCO ultimately played in desegregation.

The exhibit highlights that while METCO was focused on monitoring and resolving racial imbalance issues in school placement, there were also problems that needed to be dealt with internally. Documents included in the exhibit range from letters of petition from different organizations to Boston officials that were monitored and sometimes filtered through METCO. Letters from executives in METCO to officials in the Boston School system imploring them to aid in making school desegregation an easier process for students and organizations helping in communities. Some of these letters will show not only the frustrations of grassroots organizations and major organizations like the NAACP branch of Boston, but also the problems faced by METCO in regards to representation of their work with desegregation and student placement.