The Decision

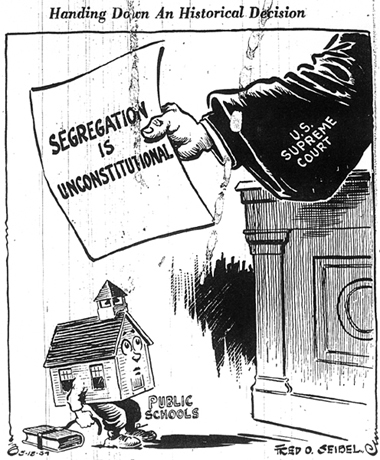

Political cartoon, 1954. Image courtesy of the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia. Reproduction not permitted without prior permission, in writing, of the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia.

On June 21, 1974, Judge Garrity filed his 152-page opinion and order in the Morgan v. Hennigan case, which lasted approximately fifteen days, siding with the NAACP. He stated that the Boston School Committee “…intentionally brought about and maintained racial segregation in the Boston Public Schools.”[1] In his order, Judge Garrity determined that with the new school year beginning in September 1974, the State Plan submitted by the Board of Education would go into effect in Boston Public Schools, confirming the order of the Massachusetts State Supreme Court from earlier that year. Within the opinion, Garrity made it clear that “no amount of public or parental opposition will excuse avoidance by school officials of constitutionally imposed obligations.”[2] He emphasized that the integration of races in public schools desegregation could not be avoided any longer by the Boston School Committee who were already gearing up for a fight against this decision. Ronald P. Formisano, author of Boston Against Busing, posited that “Garrity took exceptional care to make his opinion dovetail with earlier decisions of the Massachusetts Supreme Court. Garrity wanted, above all, to present an order that represented ‘united judicial authority.’”[3] Garrity came into the spotlight by bringing mandated or “forced” busing to Boston; because of unpopularity of busing, Garrity became the center around which many busing opponents focused. Although blame and criticism fell on Garrity, many noted frequently that he could not have come to any other decision based on the evidence and any judge would have made the same conclusion. The pages below provide a sampling of the opinion offered by Judge W. Arthur Garrity in Morgan v. Hennigan.

The decision rendered by Garrity considered all prior cases regarding desegregation within and outside Boston and Massachusetts. This decision relied on those earlier decisions to set fourth principles, which Garrity later implemented. He found that the Boston School Committee was guilty of creating a dual system of segregated schools against the best interest of the student population. The Committee had made decisions that perpetuated racial segregation in public schools; he noted, “this occurred in 1968 when certain streets in the Cleveland junior high district, 91% white, were transferred to the Russell junior high district, 85% white, and to the South Boston high, 99% white” creating overcrowding rather than utilizing the open seats in King which was predominately black.[4] Garrity also noted that in constructing new schools, the committee approved those “built near racially segregated housing projects.” This process sustained racially segregated schools.[5] After 147-pages of evidence and analysis, Garrity penned a “remedial guidelines” section, focusing on the future.

"The defendants must eliminate all vestiges of the dual system 'root and branch'."

~Arthur Wendell Garrity, Jr.

Garrity outlined that the school committee could no longer stand neutral, as had been their stance, in this issue because that was “no longer constitutionally sufficient”.[6] The school committee had always maintained that they did not cause segregation. In the decision, Garrity simply destroyed this stance and called for the committee to finally step up. He set forth that the primary responsibility for desegregating the schools fell to the Boston School Committee, as it had always been, and their lack of gusto so far must end. Garrity considered carefully all the steps needed to reverse the segregation that had been maintained and continued. He voiced that “busing, the pairing of schools, redistricting with contiguous and noncontiguous boundary lines, involuntary student and faculty assignments, and all other means, some of which may be distasteful to both school officials, teachers, and parents”[7]would be placed into effect as needed. In conclusion, Garrity expressed that the methods of desegregation present in the plan were open for discussion at the next scheduled hearing.

Following the decision, opposition to the State Plan was tumultuous. It begs the question why Judge Garrity selected the State Plan over those submitted by the School Committee. According to the Board of Education and the other courts, one did not exist. Robert Dentler, Dean of School of Education at Boston University, believed that “At that time, the Boston school committee had no plan for desegregating its schools. It had refused directives from the state board of education to prepare and execute such a plan…”, although that was not entirely correct.[8] The school committee had produced plans for desegregation, several of them in fact, but the committee was set against redistricting and busing as modes to bring about desegregation. Many of the school committee’s plans relied on voluntary school assignments for desegregation. Therefore, the Board and the courts rejected all plans submitted by the school committee as little more than showboating. They continued to argue that segregated neighborhoods produced segregated schools and the school committee could not change that. As the School Committee had had since late 1965 to submit a satisfactory plan for desegregation and had not, Garrity left with no decision other than to implement the only viable plan for desegregation. Many criticized the decision Garrity made to implement the Board of Education's plan for desegregation, as it was believed this plan did not have valuable input and vital information from local agencies and parents.

References

[1] W. Arthur Garrity, Tallulah Morgan et al., v. James W.Hennigan et al. Opinion. United States District Court District of Massachusetts Boston, Massachusetts, 1974: 1.

[2] Garrity, 149.

[3] Ronald P. Formisano, Boston Against Busing: Race, Class, and Ethnicity in the 1960s and 1970s (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991) 67.

[4] Garrity, 50.

[5] Garrity, 125.

[6] Garrity, 148.

[7] Garrity, 149.

[8] Robert A. Dentler, “Desegregation Planning and Implementation in Boston," Theory into Practice, vol. 17, no. 1 (Feb., 1978): 72-77. Taylor & Francis, Ltd.: 72–77. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1476156.